Happy Sunday, and thank you for subscribing to the Coaching Letter. You are awesome. Today is also Father’s Day here in the US, and I read this little appreciation of dad humor in the New York Times this morning, mostly because I really did not want to get out of bed, but it is quite touching and worth reading. My dad does not text, but there were definitely parts that made me think of him. Happy Father’s Day, Dad.

This Coaching Letter is about teams. Much of the way my colleagues and I have been thinking about improvement lately hinges on the creation and nurturing of effective teams. It would not surprise me if my colleagues were ahead of me on this, but I started thinking about what we know about high functioning teams, which sent me back to several sources that I’ve known about for a while, but looked at with a new appreciation. In short, I think we are a bit blasé about teams, and do not attend to the factors that make some teams more successful than others. So if you are a member of a team, or are hoping to create or facilitate a team, or have the work of teams as a feature of your organizational theory of improvement (that must cover just about everyone who reads the Coaching Letter, right?) then here are some suggestions for useful summer reading. The ones with links are articles, and the ones in italics are books.

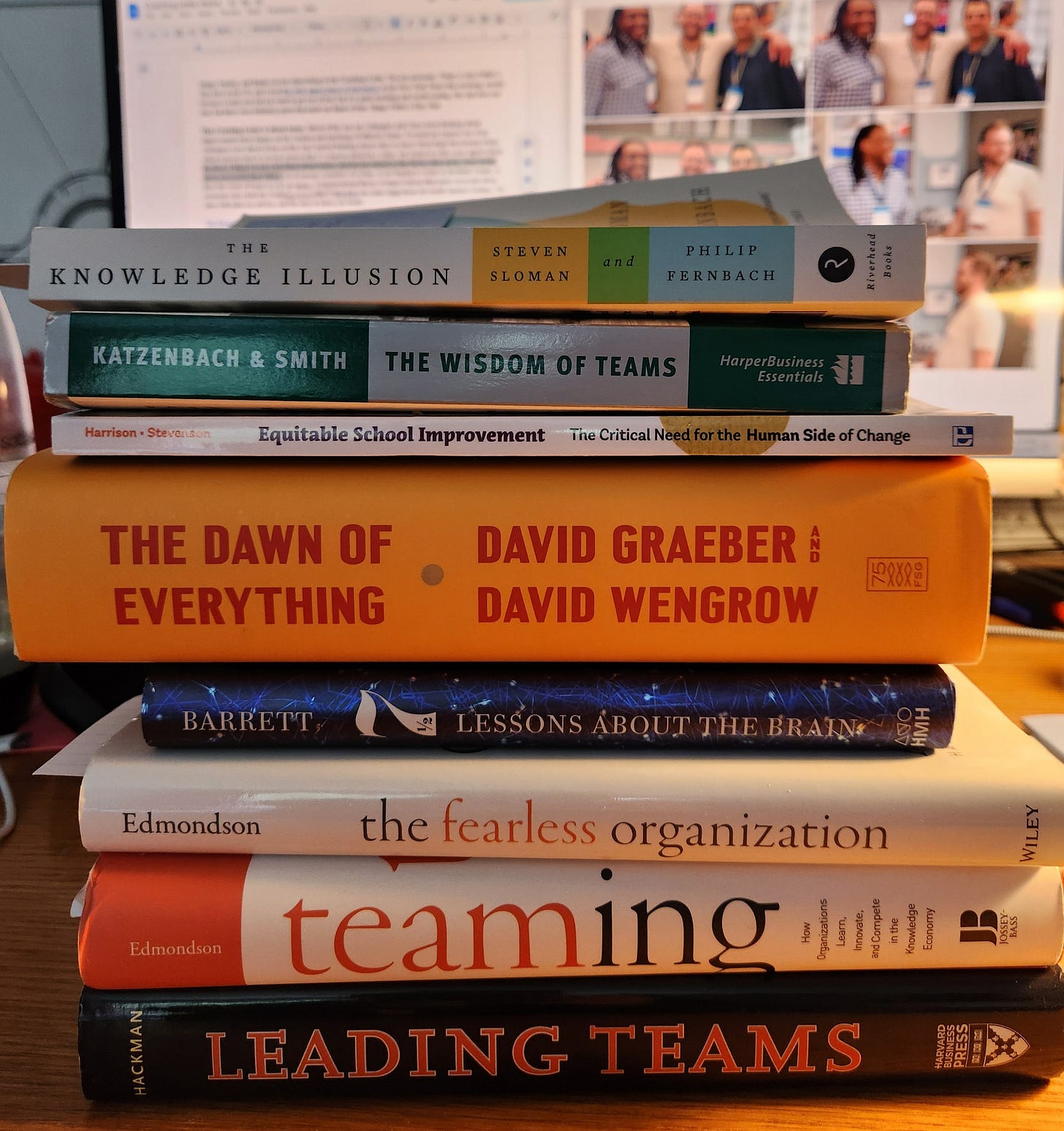

The Discipline of Teams and The Wisdom of Teams (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993) were the sources that got me thinking about teams more seriously. The authors make the argument that we should be paying attention to the formation of teams and the conditions we create for them, so while I realize that these sources are more than 20 years old, the ideas are foundational. They make the case for high-performance teams as the engine of improvement, and everything I have learned recently makes me think they were right.

And I went back to Katzenbach & Smith because I listened to this Hidden Brain podcast interview of one of the authors of The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone by Sloman & Fernbach (2017), which is one of my new favorite books; please forgive the long excerpt, but I really want to include the part about Vygotsky and you really need the part before that so that it makes sense:

Humans can do even more than read what others are trying to do. Humans have an ability that no other machine or animal cognitive system does: Humans can share their attention with someone else. When humans interact with one another, they do not merely experience the same event; they also know they are experiencing the same event. And this knowledge that they are sharing their attention changes more than the nature of the experience; it also changes what they do and what they're able to accomplish in conjunction with others.

Sharing attention is a crucial step on the road to being a full collaborator in a group sharing cognitive labor, in a community of knowledge. Once we can share attention, we can do something even more impressive—we can share common ground. We know some things that we know others know, and we know that they know that we know (and of course we know that they know that we know that they know, etc.). The knowledge is not just distributed; it is shared. Once knowledge is shared in this way, we can share intentionality; we can jointly pursue a common goal. A basic human talent is to share intentions with others so that we accomplish things collaboratively.

These ideas are due, in large part, to the great Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who in the early twentieth century developed the idea that the mind is a social entity. Vygotsky argued that it is not individual brainpower that distinguishes human beings. It is that humans can learn through other people and culture and that people collaborate: they engage with others in collective activities.

Which reminded me of a couple of other things as well…

Seven And A Half Lessons About The Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett (2020). Kerry and I were using Barrett’s work so much at one point that we started referring to her as LFB. Anyway, she writes about the brain in almost poetic terms, and the descriptions about how our brains interact with the brains of others is quite amazing—see the chapter called “Your brain secretly works with other brains.”

The Dawn of Everything by Graeber & Wengrow (2021). My colleague Andrew sent me this book as a gift recently, and it is a barn-burner of a book. Every couple of pages there is something that sets you back on your heels. I can’t think of anything else that has challenged what I thought I knew as much as this book. But what is relevant to this list of sources on teams is what they say about the influence of others on how we think:

When we are capable of self-awareness, it’s usually for very brief periods of time: the ‘window of consciousness”, during which we can hold a thought or work out a problem, tends to be open on average for roughly seven seconds… the great exception to this is when we’re talking to someone else. In conversation, we can hold thoughts and reflect on problems sometimes for hours on end.

If that is not an argument for coaching and teamwork, I don’t know what is.

The section on teacher teams in Equitable School Improvement by Harrison & Stevenson (2024) is ridiculously good and you should buy the book immediately. Seriously.

What Google Learned from its Quest to Build the Perfect Team. This NYT Magazine article is something of a modern classic, and introduced Amy Edmondson to a much wider audience, and in particular the concept of psychological safety. Google’s Project Aristotle found that the single most important factor in high-performing teams is whether team members feel safe to take interpersonal risks — to ask questions, admit mistakes, challenge each other, or say something weird without fear of looking stupid. The personalities of the team members are not as important as their behaviors—many of you have heard us beat that drum repeatedly—and those behaviors, such as conversational turn-taking, encouragement, and sensitivity to concerns, can be learned. The conditions for psychological safety rest as much outside the team itself, with leaders modeling vulnerability, normalizing and even celebrating mistake-making as the path to learning, and removing evaluation, judgment, and accountability for results.

Two of Amy Edmondson’s books are largely about teams, and are both really useful and enjoyable to read: Teaming (2012) and The Fearless Organization (2018). The former is mostly about teams as drivers of learning and innovation and the latter is, as far as I know, the most comprehensive treatment of psychological safety as a performance driver.

Zombie Leadership. An article about outdated ideas about leadership that refuse to die, including how important individual leaders are versus the work of teams.

A Theory of Team Coaching. This one is particularly geeky, and is most useful for educators who coach or facilitate teams. But it does contain some very useful points for leaders to be aware of, particularly that the research shows that focusing too much on interpersonal relationships doesn’t reliably improve performance. In fact, good performance often leads to better relationships—not the other way around. Those of you who have come to our workshops will recognize that drumbeat, also… And leaders should ensure that the work of the team allows for real teamwork (i.e., members are interdependent); structures and rewards support collaboration, not competition (remember that rewards are not always tangible, but include expressions of what the organization values; and the team has the information and tools it needs. Oh, and no amount of coaching can make up for a lack of these things. Hackman also wrote Leading Teams (2002).

Senior Leadership Teams by Wageman et al. (2008). Another classic. This one, while particularly about senior leadership, has some gems that are applicable to all teams; I included some of them in this slide deck which I put together years ago for a purpose I don’t exactly remember. My favorite, which intersects with our work on strategy and strategic planning:

A lack of shared understanding of strategy arises when team members are not given the chance to calibrate their understanding of how the words in their strategy documents translate into organizational action.

And before I close, I want to take a moment to acknowledge the passing of someone who exemplified the best of what leadership and collaboration can look like. Andrew Lachman was the executive director of Partners for Educational Leadership (under our old name: Connecticut Center for School Change) when I joined the organization in 2013. Andrew had many qualities that I deeply appreciated. He was a big thinker, he was very sharp, and he knew a lot. He managed to not suffer fools gladly and be really kind and generous both at the same time. He was not shy about telling you what he really thought. I found myself talking at Andrew quite a lot, and he never seemed to mind although I do think he thought I was a bit naïve at times, and I realize that he was a great example of what happens when you just keep quiet and let the other person talk. Also, I think the term “twinkle in the eye” was invented for Andrew. May his memory be a blessing.

As always, if there is anything I can do for you, please don’t hesitate to reach out. And if you are just about to go on summer break, have a lovely time and a well-deserved rest. Best, Isobel