Hello and thank you for subscribing to the Coaching Letter. You rock. Thanks to a combination of factors—Kim Marshall featured Coaching Letter #213 on Task in the Marshall Memo, quite a few people shared Coaching Letter #214 on why teaching is so complex, and several other Substack authors recommended my work on their pages—there are more new subscribers than usual lately. So welcome, and just so you know, I write about whatever aspect of my work is taking up space in my head at any given time, which includes instruction, psychology, leadership, coaching, strategy, equity, and my not-always-successful quest to be a better human. The Coaching Letter is free and you are welcome to use it in your work if it’s helpful. This comes to you courtesy of my organization, Partners for Educational Leadership.

My fabulous colleague Kerry and I run two recurring coaching workshops. There is the Coaching Institute in the fall (Click here to sign up—you should come! It’s fun and interesting and you will be challenged to think differently about lots of things you thought you knew) and The Coaching In-Depth, which is coming up next week. This year we’re focusing on high school, and we’re going to be leaning heavily into the work of Donella Meadows, who wrote a great book called Thinking in Systems. I highly recommend it. So this Coaching Letter is an extended version of what I’m planning to say at the workshop.

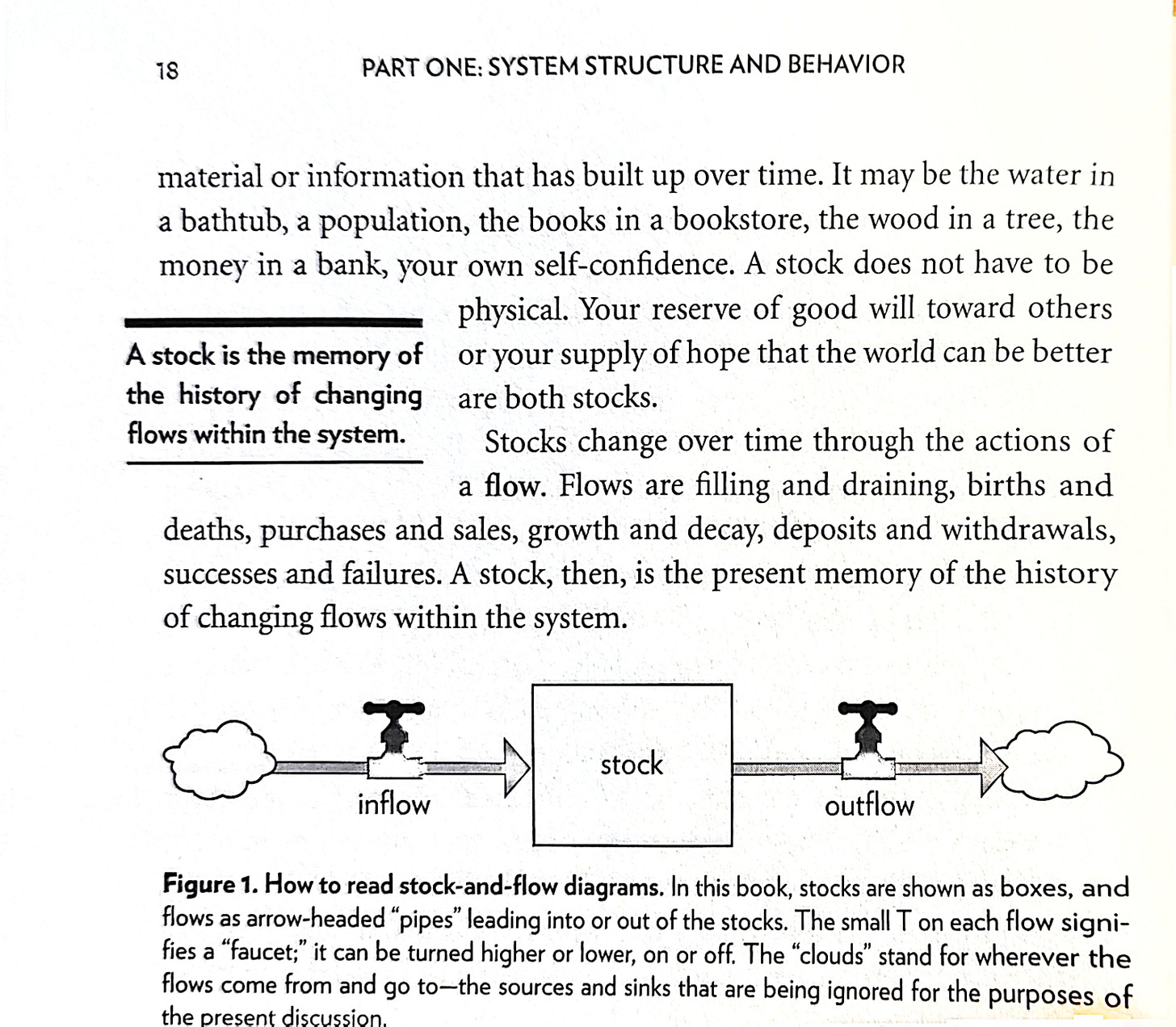

I listen to Rachel Maddow’s news show via podcast the morning after it airs. I like it because she often starts with a bit of political history and I often feel like I learn something. In the episode aired May 5 (but posted May 6, here’s the link on Spotify), she started with a catalog of incidents and near misses involving airplanes in US airports and airspace since President Trump was inaugurated. And there are an alarmingly high number of them. Maddow points out that the new Secretary of Transportation, Sean Duffy, does not have the qualifications that you might expect someone in that position to have, and she plays a clip of him talking about the outdated technology to illustrate his ineptness. She draws a direct line between Trump’s assumption of power and the increase of incidents and near misses. But while her facts about the incidents may be correct, she’s wrong about the cause. She seems to think that aviation safety is a switch that you can flip with the firing and hiring of who’s in charge, rather than a capacity that has to be built and maintained over time—more like filling a bathtub than flipping a switch. Donella Meadows called it a stock.

The underlying issue with aviation safety in the US is that the system relies on several stocks, which have been degrading over decades. In particular, the technology on which the system depends is outdated and wearing out (the new Transportation Secretary is right about that), and the supply of air traffic controllers is low and declining. For a much more nuanced examination of what’s going on with air travel, listen to the coverage by The Daily (which is a podcast from the New York Times that posts at 6 every weekday morning). This episode of the podcast is about the really serious issues involving air traffic control at Newark. (This is personally salient to me, because my dad lives in Edinburgh (hello, Dad!), and the only direct flight to Edinburgh from the east coast is out of Newark, so I fly from Newark at least twice a year, and will be doing so again in August.) The reporter interviewed for that podcast makes it clear that the system is complex, that these problems have been building over time, and that there are multiple possible causes that interact with each other.

What I learned from The Daily is that once air traffic controllers have graduated from the FAA’s academy in Oklahoma City, they are first of all assigned to less busy airports, and work their way up to the most challenging ones, like Washington National and Newark. It takes years. You could hire thousands of them tomorrow and it would not have an immediate impact on staffing at Newark. In addition, the problems that Newark is now experiencing can be traced in part to relocating air traffic control for Newark to Philadelphia, a change that was intended to improve the system but had unintended consequences. This is a nice illustration of the difference between complicated and complex that I wrote about in CL #214—in complex systems, you can’t always predict what results a change will bring about, and often cause and effect are separated in time and space. This is the mistake that Maddow made—she thought that change in leadership in the FAA and the Department of Transportation is the cause of the problems now happening, because they happened so close together in time. But correlation is not the same as causation, and just because things happen close together—in space or time—does not mean that they are cause and effect.

Getting switches and bathtubs confused leads to assumptions about problems that are incorrect, and therefore to possible solutions that won’t help.

Just to be clear, Trump also doesn’t seem to understand the difference between bathtubs and switches. When he talks about tariffs, he seems to think that imposition of them today will lead to more toys, t-shirts, and televisions being manufactured in the US tomorrow. That’s not going to happen. It takes years to build factories, re-orient supply chains, and train workers. Companies know that Trump is going to be out of office before they could accomplish all those things. And when Trump talked about air traffic controllers, he told Elon Musk to hire geniuses out of MIT, when it takes years to refill that stock and there is no evidence that geniuses make better air traffic controllers, and probably lots of reasons to suggest that they wouldn’t.

Donella Meadows, by the way, is one of my heroes. She was the lead author on The Limits to Growth (a classic in environmental studies), a MacArthur Fellow, and taught at Dartmouth College for nearly 30 years. She died in her fifties, but if she were alive now she would be a TED Talk sensation—she had a genius for explaining complicated topics in simple terms. Here is a great essay on silver bullets that everyone who leads a system or is supposed to write an improvement or strategic plan should read—another reminder to leaders that you really should be able to describe your system before you try to change it. Also, note the importance of paradigms (AKA deep and powerful mental models); as Robert Pirsig wrote in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance:

If a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory. If a revolution destroys a government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves… there’s so much talk about the system. And so little understanding.

And if you really want to geek out you can watch Meadows teach about modeling systems to college students at Dartmouth in 1977. And although, unfortunately, we don’t have anything in the way of short videos of Meadows, here is a nice wee video that illustrates some basic principles of systems, such as the nestedness of systems, feedback loops, stocks, and complexity.

My favorite way to teach about systems when I was a 9th grade geography teacher was to have students read “Top of the Food Chain” by T. Coraghessan Boyle—it’s a short story originally published in Harper’s Magazine in 1993 (available to Harpers subscribers here and you can also get it on Scribd). It is funny and sad and based on a true story of American intervention in Borneo to kill malaria-bearing mosquitoes, illustrating how good intentions can easily turn to farce when you don’t understand the system you are dealing with—and, when it comes to complex systems, you can’t necessarily predict how the components of a system will interact with a newly introduced element, and each other, to produce surprising and sometimes disastrous results. I used it to teach about systems by having the students graphically represent all the connections and the interactions among them described in the story, which turns out to be a lot.

In case it isn’t obvious already, we are drawing on systems thinking to talk about high schools because they are complex systems, they function using stocks that have built up over time, and as a result changing them is not easy, especially because we don’t do a good job of understanding them, and we tend to treat those stocks as liabilities rather than assets—and, as I’ve already talked about, when it comes to complex systems, you can’t necessarily predict how the components of a system will respond to efforts to change the system, often producing unexpected results. As Donald Schön (1987) put it:

In the varied topography of professional practice, there is a high hard ground overlooking the swamp. On the high ground, manageable problems lend themselves to solutions through the application of research-based theory and technique. In the swampy lowland, messy, confusing problems defy technical solution.

(The Pirsig and Schön quotations are currently slides 62 & 63 in the Coaching Letter Slides)

As ever, please let me know if I can do anything for you. I very much appreciate all the people who respond to any given Coaching Letter, it’s the main reason why it’s such a rewarding endeavor. Best, Isobel

Feel this in my bones. Left higher ed teacher prep to immerse myself back into public schools so I could be in the messy swamp, closest to the point of impact - inside the system the academics published to one another about. It’s a both tough and delightful to see theory play out - and shaped - as it does in lived context - as long as we can remain flexible and continue to be reflexive, responsive, and not drown in the deep waters of systems change.