Good morning, I hope you are well. I know it’s only a couple of days since the last Coaching Letter, but today is a snow day in most of Connecticut so I picked up some time I wasn’t expecting to have. So to continue the Black History Month theme, this CL is about critical consciousness, a term credited to Paulo Freire. Rydell and I wrote about critical consciousness in Equitable School Improvement, and then I just had to write about it again for another book proposal, so here’s a variation on both of those:

Critical consciousness is the understanding that current systems and societal structures are the result of generations of systemic attempts to perpetuate power structures that favor White people over non-White, male over female, Christian over non-Christian, and many other variations of hegemony and oppression. Many of our systems, therefore, reflect the mental models of those who hold power over others. Critical consciousness, therefore, includes the ability to see those mental models manifested in the world around us, and the willingness to challenge them, change them, and mitigate their impact.

If you need a quick refresher on mental models, here’s a Coaching Letter about the idea.

Here’s my go-to example of my developing a critical consciousness. I read geography at university, and I remember being in the School of Geography library reading a journal of feminist geography, whose title and author I don’t remember. I don’t even remember the topic. I mean, this was 40 years ago. But I do remember the example of one of Britain’s new towns. Britain, after the second world war, had to rehouse considerable numbers of people from urban areas that had been bombed by the Germans (“the Blitz”). But many of these areas were considered to be substandard anyway, so they were rebuilt at lower population densities, and in addition, new towns were created on what had been farmland through the New Towns Act of 1946—places like Milton Keynes, Stevenage, and Cumbernauld. These places frequently had a small village at their center, but other than that were designed from scratch. And so they reflected what the planners considered to be desirable features of a modern town, including the separation of cars from pedestrians. Which I can certainly sympathize with. So there are places in the new towns (although they were all designed and built separately from each other) where the roads are at a lower level, and the pedestrian walkways are at a higher level in park-like settings. And the roads go in a straight line, and the walkways meander through the park.

I had seen this, because one of my school friends had moved to Cumbernauld with her parents when I was in high school. But what had not occurred to me, but was pointed out in the article, was that the pattern reflected the mental models of the designers who, in the 1950s when Cumbernauld was created, were probably all men, thought that cars should go from place to place in a straight line, but pedestrians, who would have included women carrying shopping bags and pushing prams, had nowhere to be in a hurry, and would prefer the sine curve aesthetic over the efficiency of the straight line. But anyone who has ever been in a park or a college campus and seen how pedestrians have worn a path in the grass where one was not laid knows that most people, most of the time, just need to get somewhere quickly. Anyway, when I read the article, I realized that I had walked those winding paths carrying heavy shopping bags, but it had not occurred to me to question why they were winding. It was a very good lesson in paying attention to why things are the way they are, who benefits, who suffers, and whose mental model of what ought to be is dominant.

Privilege is having the option to ignore, deny, or minimize any problem, challenge, or indignity because it does not apply to you. One is acting on one’s privilege when one exercises that option. Critical consciousness, then, includes recognizing that privilege despite not having direct experience of a problem, which is difficult because we are wired to operate on the basis of our own lived experience and devalue or dismiss the experience of others. When we hear about someone else’s plight, or read about an injustice, our tendency is to think things like “I would have been able to handle that” or “it can’t have been that bad” or “they must be exaggerating” or “they must have done something to cause that”. This phenomenon has acquired a name, victim-blaming, in some instances of this thinking, but it happens all the time even when there is no victim per se. We tend to minimize others’ reports of pain, for example.

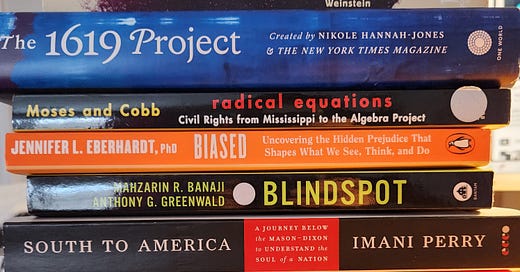

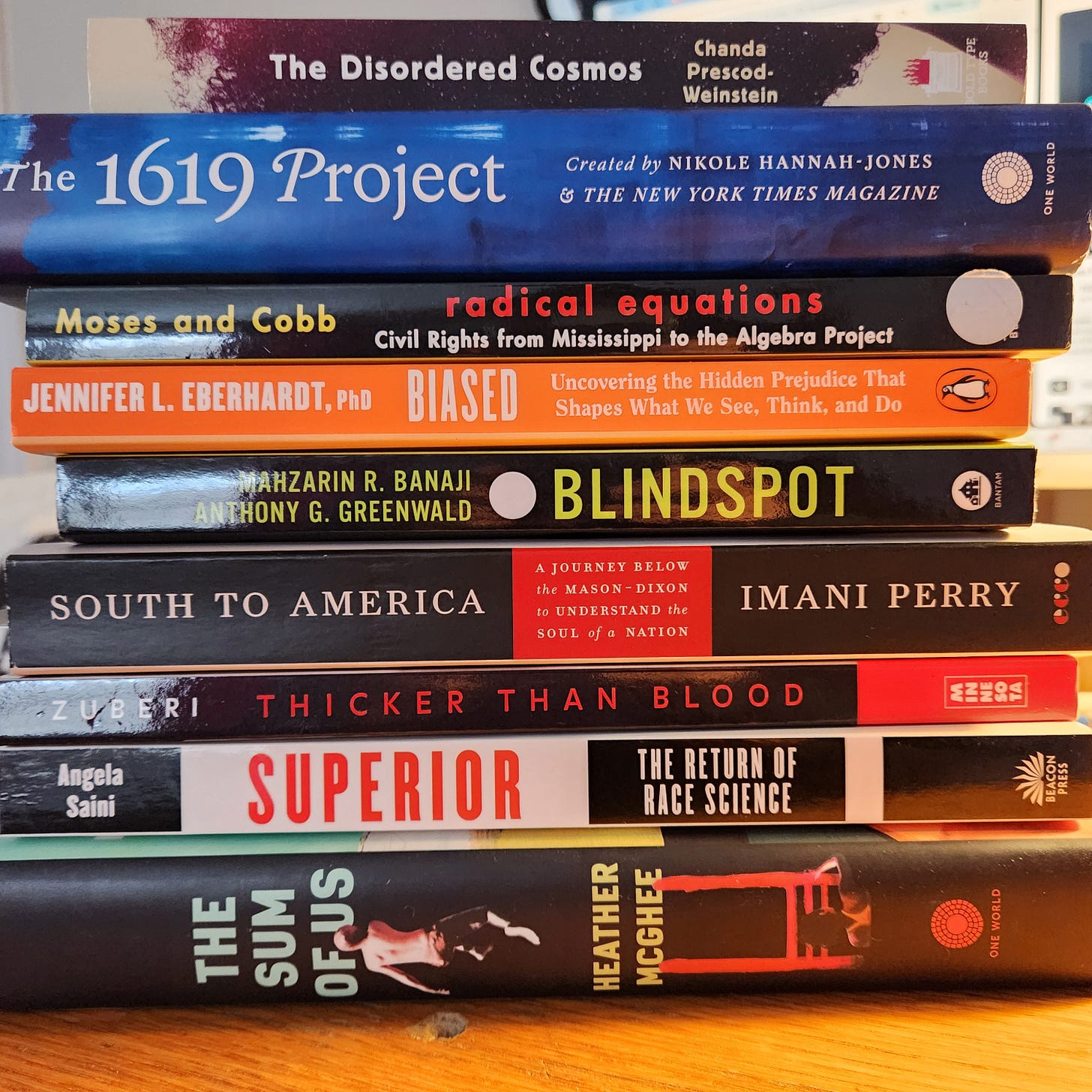

So I recognize the need to recognize my privilege and continue to develop my critical consciousness. And so here are some books that have helped me to do that. These ones are relevant to Black History Month, and are deliberately counter to the most popular flavor of Black History Month, which is to tell the story of an African-American who overcame some challenge or was the first African-American to do something, without asking why they had to struggle or were the first. I picked books that educators are less likely to have heard of, because I think that’s what a lot of people look to me for. These are in no particular order.

Jim Crow's Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership, by Leslie Fenwick. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas has been portrayed as a landmark civil rights decision that was a precursor to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. I’ve even been to Topeka, where there is a marker to commemorate the decision. But not so fast. What happened after is that thousands of Black educators lost their jobs during school desegregation, even when, which was often the case, they were better qualified than their White colleagues. Here’s an interview with the author. And here’s an episode of Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast that asks why we forgot what happened to Black educators after Brown.

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, by Bryan Stevenson. Whatever you think you know about the criminal justice system as experienced by African-Americans, it’s worse. Here’s an interview with Mr. Stevenson, and of course you can always watch the major motion picture.

Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race by Margot Lee Shetterly. This book surprised me in a different direction—it had not occurred to me that there would be Black mathematicians involved in the effort to put a man on the moon, let alone rooms full of Black women. This is their story. You can also watch the movie, but know that it has been turned into a White Savior narrative, which is not the tone of the book. Here is Margot Lee Shetterly being interviewed by Adam Grant.

The Disordered Cosmos by Chanda Prescod-Weinstein. I think a lot of people would be surprised to know that Neil deGrasse Tyson is not the only Black astrophysicist. This book is about why Professor Prescod-Weinstein loves her subject so much, but is also a critical examination of why there are not more Black academics in the hard sciences. You can find video/audio of her on this page of her website.

The 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones. This book started as a special issue of the New York Times Magazine on the 400th anniversary of the first slave ship arriving in America. If you do nothing else, click on that link. I don’t know anything like as much about the history of slavery in America as I do the history of the Civil Rights movement, but I thought I was reasonably well-informed. But this point hit me: how plantations have managed to retain a romantic aura, and how we would think about them differently if we called them what they were, forced labor camps. Nikole Hannah-Jones is a bit of a hero of mine, because she is brave in the topics she writes about, and she is a really great writer. There is also a 1619 podcast.

Superior: The Return to Race Science, by Angela Saini. This is a really expansive history of racist ideas in both human development (biology) and human society (sociology). It covers the beliefs that allowed slavery to flourish, the racism of Victorian scientists such as Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton that laid the groundwork for so much racist science that followed, and more recent controversies such as Cheddar Man. It’s an easy read and does a nice job of showing how there is no such thing as objective, and that science is no more immune from our biases and stereotypes than any other facet of life.

The Sum of Us, by Heather McGhee. This book was also jaw-dropping, along the lines of I-can’t-believe-I-didn’t-know-that. The most stunning case she writes about, to me at least, was what happened to the public pools in the wake of forced desegregation. I knew about stuff like this happening, but I didn’t know how large some of these pools were, and therefore how large the sacrifice some people were willing to make in order not to have to share what they had with people of a different skin color. The book also has an extensive discussion of the zero-sum mentality, and is worth reading for that alone. Heather McGhee was the keynote speaker at the last Carnegie Summit, and she was great. When she left the auditorium, the people who were outside stood and clapped as she walked by, it was a super cool moment. Here is a podcast interview.

Thicker Than Blood: How Racial Statistics Lie, by Tukufu Zuberi. Couldn’t leave this one out, even if it is a much more technical book and took me a long time to read and process. I read it because, when Rydell and I were starting to write Equitable School Improvement, he asked if I would draft the chapter on data. I remember this well—we were sitting in Rein’s Deli in Vernon, and I had this feeling of dread wash over me, but we were on a tight timeline and it didn’t make sense to argue over it, and he was going to write other parts that I knew were also going to be hard. So during the summer I holed up for about three weeks reading about data and statistics and their intersection with bias and stereotyping, but especially racism. This book was eye-opening, and I could not have written the chapter without it. So I wrote to the author when the book came out, and we had a lovely correspondence over several emails, and it was only later that I discovered that he was, among many other accomplishments, one of the hosts of the TV series History Detectives. My big take-away from the book, which I kinda knew but hadn’t really fully understood, is that much of the time when we talk about race in research, we succumb to the easy trap of thinking that race is the cause of whatever the measurable outcomes are. But almost always, race is not the cause, it is how people respond to race. And I work hard to always keep that in mind. It reminds me of the famous line from Peter Senge, “how you see the problem is the problem”, which brings me back to the beginning of this Coaching Letter, to CL #72 on mental models.

I hope you can find the time to read some of these great books. I would love to hear about it if you do. Best, Isobel