Friends, I hope this finds you well. Most of you are now on winter break, and I had so hoped to get this written before then! Oh well. If you are not reading this until after you get back from the holidays, I hope you had a lovely time! And if for some reason you actually do read this over break, I hope you are getting some rest! You need it! In any case, thank you for subscribing to the Coaching Letter. You rock.

This Coaching Letter is mostly about upcoming work, much of which is in-person, fee-for-service work, so I will understand if you want to skip this one… But there is also a lot about our most recent thinking, so if the shameless plugging doesn’t bother you, you should stick around. And if you just want to cut to the chase, here’s the link to the workshops in Fairfield, CT, Providence, RI, and Southwick, MA that I’m hoping you’ll sign up for.

I’m going to start this story with the outbreak of the pandemic in the spring of 2020. We—my colleagues and I at PEL—worked overtime trying to be helpful to districts struggling with how to contend with so much disrupted schooling. We produced so much work during that time that I don’t remember all of it. But, at least from my perspective, there are several big bodies of work we started during and since that time that have turned out to be really significant.

The first was the Accelerated Learning Framework, which we produced to help districts with decisions about where to focus their efforts: prioritize essential concepts and skills; design academic tasks as deep-learning experiences; practice responsive teaching based on formative real-time assessment; scaffold learning and prerequisite skills; and center student self-efficacy in instruction, task design and classroom culture. Many of the current readers of the Coaching Letter will remember participating in one of the workshops we ran in 2020 and 2021; most of them happened during the Zoom Era, and then later we ran them as in-person retreats and workshops. (There’s a slightly longer version of this story here, and a much longer version in this article published in Learning Forward’s magazine, The Learning Professional, and featuring one of our partner districts, Wilton. Yay, Wilton!).

Since then, we have developed a more instruction-focused version of the Accelerated Learning Framework, which I talk and write about all the time—for example, here’s how I wrote about our model in this particularly caustic post about an article by Carol Ann Tomlinson.

All kids should be engaged, to the greatest extent possible, in grade level content. We understand that this is not universally possible, and there may be very good reasons for teaching particular skills and content that are stipulated in other grade levels, but grade level should be the norm, and should not be within the purview of an individual teacher to alter, despite what Tomlinson says about curriculum design.

All kids should be engaged in meaningful tasks that give them the opportunity to connect new knowledge and skills with their existing schemata, and when I say meaningful, I mean require meaning-making on the part of the students.

All kids should be asked to make their thinking visible, so that…

The teacher can respond to the learning that’s going on in the classroom IN REAL TIME. This is a very important point. The method in Peter Liljedahl’s Building Thinking Classrooms is a fine example of how to do it, although he calls it keeping students in Flow. Tomlinson, on the other hand, gives the example of Shyla, a 4th grade teacher, who gives an assignment (that is differentiated without Tomlinson’s calling it differentiation) and then the teacher holds her breath until the students turn in their assignments days later! I don’t know what Tomlinson thinks formative assessment is, but this teacher isn’t doing it.

All students should experience a classroom holding environment where they feel both challenged and supported. I have written about this a lot: Coaching Letters #178 and #179.

The model has had several names, and the latest version is the HEAT, standing for Heuristic for Equitable and Adaptive Teaching, a visual of which you can find as Slide 8 in this slide deck. It’s useful for many reasons, not all of which were obvious to me the first time I generated it (which was, by the way, in the principal’s office at Waterbury Career Academy—he and I were talking about what to focus on when observing instruction), but I will sum up by saying that 1. It focuses on practices that are most likely to induce thinking and engagement by all students (hence the equitable part), 2. It is memorable, and 3. It is just the right balance of simple and complex.

The second was the Networked Improvement Community (NIC) that we started in spring of 2021, based, at least to begin with, on the work of Bryk & colleagues in Learning to Improve. It started as a network of six districts, and the membership has morphed a bit since then, but big shout out to Guilford, Manchester, and Naugatuck, who have been with us since the beginning. The purpose of a NIC is to pool efforts at improvement, in part by all trying the same change idea and sharing the same data. Our NIC (actually, we now have two, one in Connecticut and a new one this year in Rhode Island) has never really functioned that way, for complicated reasons; but the part that I am proudest of is that we have focused on instruction, and in particular on making instruction more equitable. We do that by working towards ensuring that all students are engaged with grade-level content and tasks that require them to think in multiple ways, when the research suggests that we, as a profession, have allowed pernicious expectations of what some students are capable of to create classrooms where not all students, particularly students of color and students who qualify for special education services, are expected to do challenging grade level work.

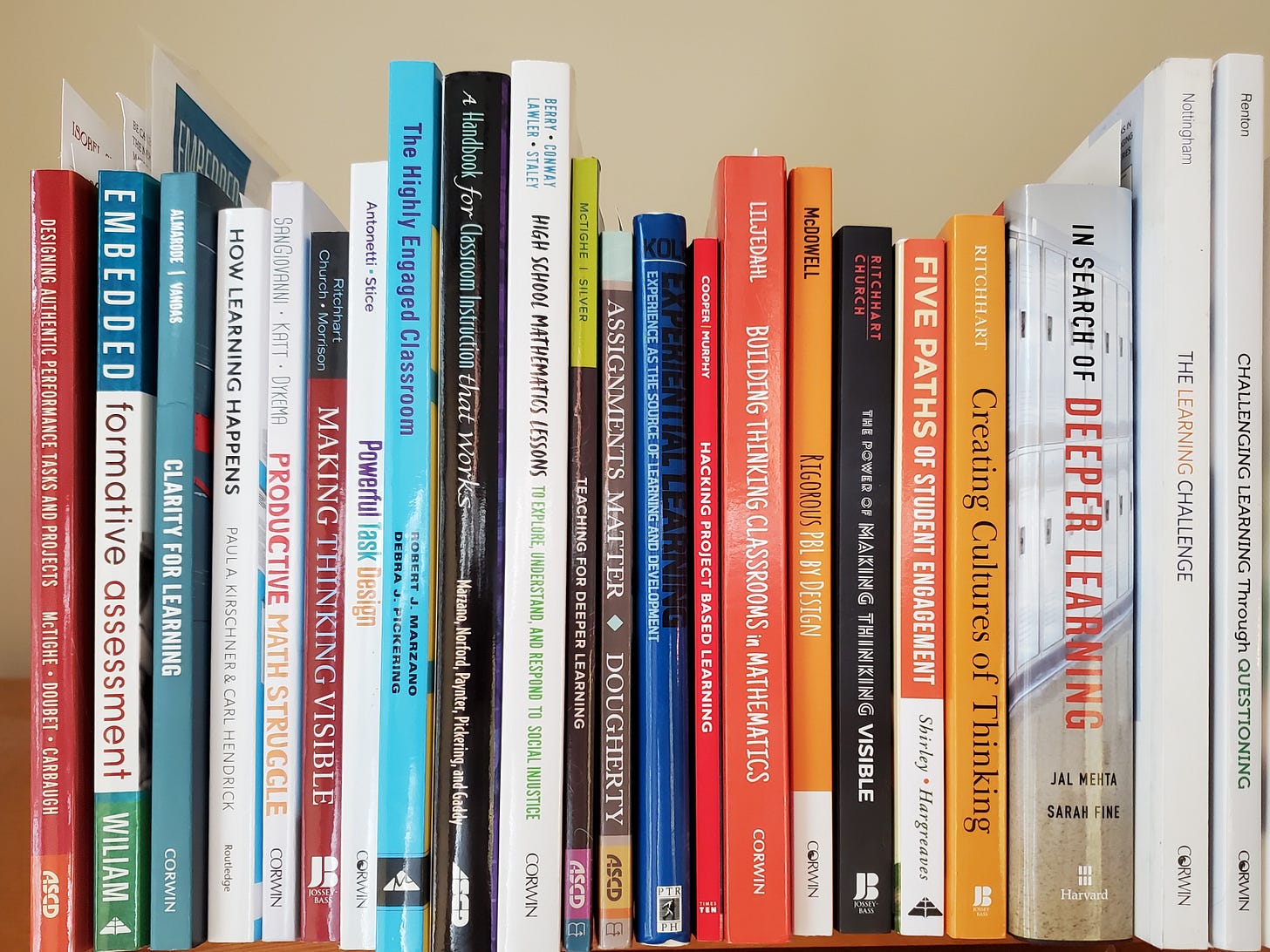

The third happened because at the end of one of the early NIC meetings, the district teams had generated their problems of practice, which were all focused on ensuring that all students are engaged with challenging, grade-level tasks, my colleague David turned to me and said something like, “We’d better get better at task, then.” And even though I was right there while the teams were working on their problems of practice, it hadn’t occurred to me that this might mean I had to do some research until he said that. So I did what any sensible person would do at that time (which I wouldn’t do now), I tweeted a request for people to send me their best resources on task. Which provided me with a list of 23 books to mine for useful information—that’s the picture accompanying this Coaching Letter, which I took for the first slide deck we created on Task (out of date now, but still useful)—which I dutifully read and synthesized for our early work on task, but we know so much more now!

It was Gina Rivera, who is now a principal in West Hartford, who responded to me that I should take a look at Building Thinking Classrooms (BTC), which turned out to be super helpful, and has given us all sorts of fruitful avenues to pursue. Some of those avenues are about BTC directly—we ran many workshops last year for hundreds of coaches and leaders on supporting BTC in their districts, and we are working now with several districts implementing BTC—and some are using what we have learned about getting all students engaged in challenging tasks by using some of the practices in the BTC toolkits. And of course, we have had Peter Liljedahl come to Connecticut twice now, and he’ll be back again in fall of 2025, and we ran an online book study on his most recent book. If you want to be the first to know what our new plans are for supporting BTC, you should join this mailing list.

I think Building Thinking Classrooms is of such great importance because it exemplifies the components of the HEAT: 1. It gets all kids working on grade level tasks by providing thinking tasks with low floors and high ceilings; 2. It asks students to think, a lot, and scaffolds that thinking; 3. It asks kids to make their thinking visible; 4. The teacher is responding in real time to student thinking—giving hints and extensions and other forms of support to keep kids thinking by balancing challenge and current ability; 5. It fosters, in a variety of ways, including but not limited to random grouping, a holding environment that communicates that all students belong in a thinking classroom. This, of course, is basically a repetition of the description of the HEAT a few paragraphs above.

Not for nothing, BTC has also changed the way I facilitate workshops. Random groups, vertical non-permanent surfaces (boards, or VNPSs), launching a task within 5 minutes, keeping people moving, debriefs in front of boards, no technology, including no PowerPoints, and much more… It’s not that I don’t talk (trust me, I talk a lot), but even that looks a lot different than it used to.

The final big thing was finding the book Systems for Instructional Improvement (SII) (Cobb, et al, 2018). This book provides a really clear strategic framework for instructional improvement that I use all the time. An early version of our visual for that framework is currently slide 9 in the Coaching Letter Slides, but Andrew made a better one that I’m going to start using. The book includes a really cogent argument for changing the way that that educational leaders lead; the proposed shift is away from what the authors call direct instructional leadership (exemplified by observing teachers and giving feedback) to indirect instructional leadership, when building and systems leaders create the conditions for teachers and coaches to work together to improve instruction. I wrote about that in CL #191 and #192. For many leaders, this represents a paradigm shift—the idea that instructional improvement happens because they observe teachers and give feedback has been firmly instilled in them, and the idea that there may be more effective pathways can represent a challenge to their thinking.

I mentioned above the workshops we ran in 23-24 in support of BTC—BTC for Coaches and BTC for Leaders. They were enormously popular because BTC has been such a phenomenon, and coaches and leaders in many districts have been trying to keep up with innovations that math teachers were already putting in place, and trying to figure out what they should be doing to support this work, and whether the same methods can and should be used in other subject areas—and this led to other problems of practice, such as how to bring about instructional improvement in subjects and grade levels that are “tougher” than others, and how to make changes to grading practices to better support changes in instruction. We learned a ton through running these workshops and in subsequent work, so now we are ready to take the show on the road again. So we are running “Next Level Instructional Leadership” workshops in spring of 2025, in the following locations:

February 19 & 20, 2025 – Fairfield, CT

March 6 & 7, 2025 – Providence, RI

April 28 & 29, 2025 – Southwick, MA

Here’s what else you should know. If you attended one of the BTC for Coaches or Leaders workshops, there will be considerable overlap—you should not come if you’re expecting something new and different. But you SHOULD come if there are other folks in your district who you would like to get a similar message. You can come by yourself if you like, but you will be MUCH better off if you bring a team. Speaking of teams, we have learned that teams generate much more concrete next steps if the teams are a cross-section of the organization, including central office, building leaders, coaches and teachers, so bear that in mind. We will talk about the need for a shared understanding of equitable and adaptive instruction, and you will benefit MUCH more if this is not a new conversation for you and your team.

So here are the intended outcomes for the Next Level Instructional Leadership workshops:

We aim to equip participants with actionable insights and tools to navigate the evolving landscape of education, emphasizing collaboration, equity, and innovation. Specifically:

Understand and Apply Strategic Thinking for Instructional Improvement: Develop a comprehensive strategy for improving instruction across systems, taking into account recent innovations and research in educational leadership.

Foster System-Wide Equity and High-Quality Instruction: Engage in activities that help create a shared understanding of what constitutes high-quality, equitable instruction, ensuring alignment across all levels of the educational system.

Design and Enhance Professional Learning Systems: Explore the role of professional learning, including the integration of coaches and how their work supports instructional improvement strategies.

Strengthen Improvement Infrastructure: Analyze the specific roles and responsibilities of building and central office leaders in establishing and sustaining structures that promote continuous improvement.

Transform Teacher Team Practices: Reframe traditional approaches to data teams or Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) by introducing improvement teams that focus on the rapid prototyping of impactful instructional practices.

I know that seems like a lot, and it kinda is, but we have frameworks and activities to share for all of these, and we are aiming to both make you think differently about instructional leadership in your district and give you tools for remodeling your instructional leadership practices. And it will be fun. And PLEASE pass on this Coaching Letter or the flier to others who you think might be interested. I appreciate it.

But wait, there’s more. The learning journey that I have described in this Coaching Letter is taking us more and more towards focusing on high school. I have had several conversations about high school with district leaders in the last few weeks, and I very much hope that we can parlay that interest into creating another NIC, this one focused on instruction at the high school level—and I know what you’re going to ask, and the answer is, sure, we can talk about grading, but we’re not going to BEGIN with grading. My general principle with grading is that, from an organizational change perspective, you want grading to change because it no longer meets the needs of the instructional practices, rather than changing grading with the assumption that that’s the lever to change instruction; I think that that’s a poor strategy. We tried starting a high school-focused NIC last year, but got started too late in the budget cycle for districts to include it in their plans. I’m hoping that we can pull it off this year. If you want to know more, can you let me know?

And finally, speaking of high school, this year the Coaching In-Depth in May at Mercy-by-the-Sea will focus on instructional coaching at high school, so if you are a high school coach, please sign up! The In-Depth is one of the most fun parts of my year—I get to work with Kerry, who is awesome, I get to meet new people, and I get to visit with coaches from previous workshops. And I get to spend a day at Mercy, which is a magical place. I hope to see you there.

Have I told you lately how much I appreciate your reading the Coaching Letter? Writing them makes me think, and getting your responses sometimes makes me think, sometimes makes me feel good, and frequently both. I am very grateful to be part of a community of dedicated educators who are themselves learners, and the Coaching Letter has become my major contribution, and also the source of enormous benefits. Thank you again. Best, Isobel