Hello, I hope this finds you well. Almost all of you are gearing up for the start of a new school year—I wish you all the best. It’s so important, and it’s so much work, and it’s exciting, and it’s stressful... I know all the feelings, and I miss it and don’t miss it both at the same time. And a bunch of new subscribers joined over the summer—welcome, you’re in the right place, and please share The Coaching Letter with others!

Brief update on our support for Building Thinking Classrooms: three of the Noyce Fellows at UConn are facilitating an online workshop on thin-slicing (if you know, you know...) on August 22, 1:00-2:15 pm EDT. Here’s the flyer. And here’s the registration link if you want to go directly there. Our BTC sessions for math and humanities coaches are pretty much full—please join the waitlist if you would like to attend one of those workshops, not only so that we can let you know if space opens up, but also so that we can gauge demand for other workshops. And if you need anything else BTC related, please email me or Tom.

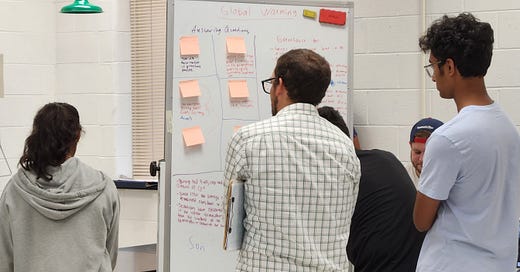

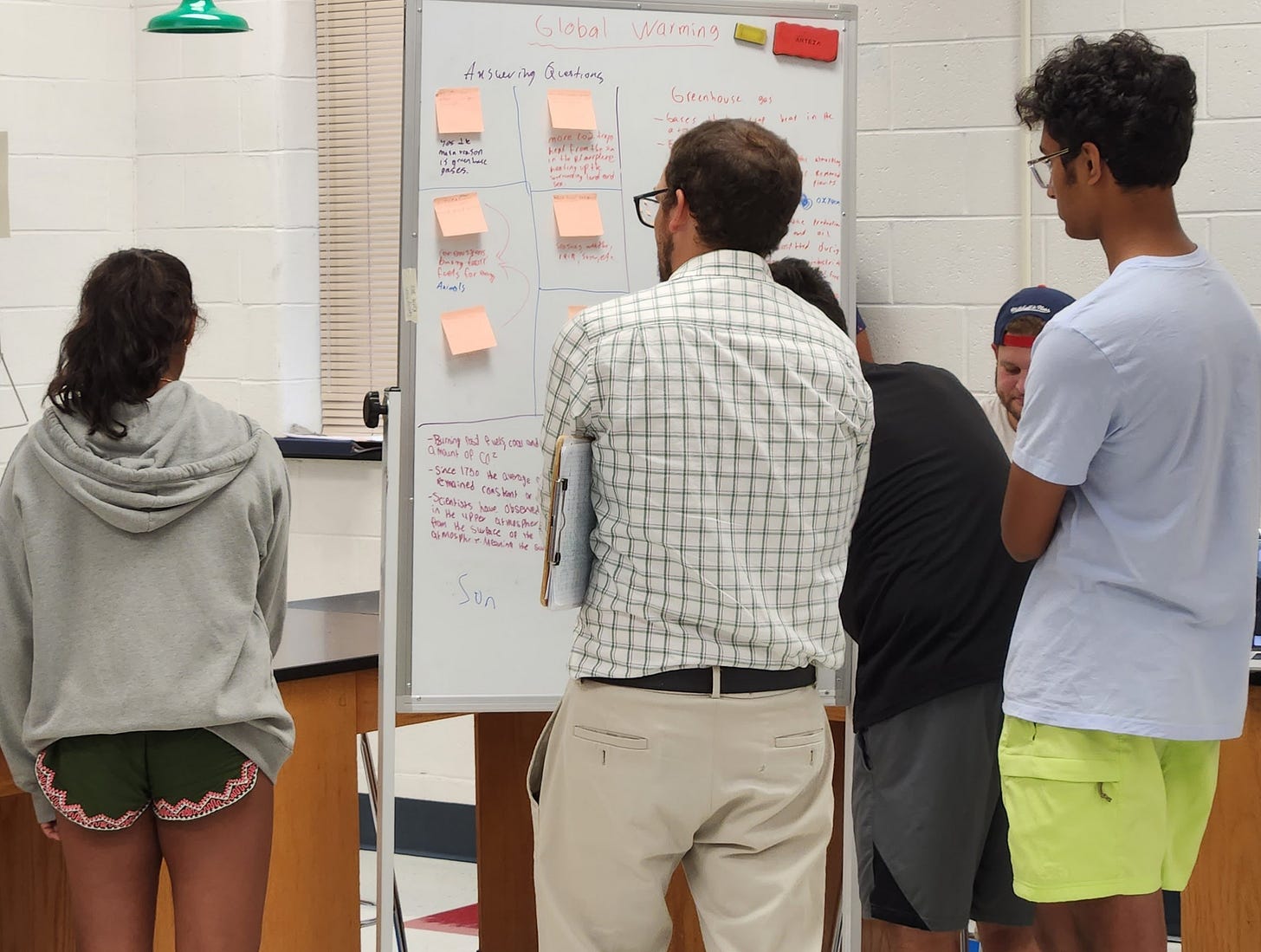

For the last several summers (except, of course, for the first year of Covid), Milford has run a very ambitious form of professional development on high quality instruction (HQI) called HQI Live! I’ve been involved with it since the superintendent, Dr. Anna Cutaia, first decided to do it, and I’m very pleased that I’ve been able to attend every season. It is a remarkable commitment of time and resources in order to create a district-wide vision for high quality instruction; this year there were something like 150 teachers, coaches, and building and district leaders in attendance, plus a huge team of facilitators, plus the four demonstration teachers, plus the tech team. Just from a logistics perspective it’s quite a feat. (If you want to know more, see CL #85, a description of, and a rationale for, HQI Live!, and CL #148, which is about the professional development practices on display in HQI Live!) Huge kudos to Milford for this work.

This year, my colleagues and I have put a great deal of thought into what exactly HQI Live! is accomplishing. At first blush, this seems like an odd thing to say—teachers watch other teachers teach and learn from that, right? Well, obviously that is true. But what’s actually going on seems to be a lot more complicated. To explain everything I mean by that would take more time than I think you’re willing to give me. So here, in this Coaching Letter, I’m just going to talk about a few of the mental models that we’re asking educators to let go of. This is important because educators’ current practices are based on beliefs about what is the right thing to do—otherwise, why would they be doing them? Teachers don’t aspire to teach poorly—in fact, we are all motivated to be competent. So if we want educators to change their practice, we need to not only support the creation of a shared mental model of what we want them to start doing (or do more of, or do more often), but also to make a case for why we want them to stop doing some of the things they are doing.

1. It’s all about relationships/it takes a long time to build trust

I have absolutely no quibble with the idea that relationships are important—indeed, I have promoted the Search Institute’s Developmental Relationships Framework (DRF) many times through the Coaching Letter, and I have a new favorite resource, the book Belonging, by Geoff Cohen. But there are two major aspects of relationship that I think are misunderstood. First is the idea that you have to build a relationship with someone before you can work with them. One of the many functions of HQI Live! is to show that a teacher can meet a group of students and have them working on a meaningful task within 5 minutes. And consistently, during the student debrief on Day 4, the students will talk about how little the typical ice-breaking activities mean to them, and how they would rather get to know their peers through working with them than through artificial relationship-building activities. (This comes up too in our coaching work, and there’s a section on this in our book, Making Coaching Matter: you demonstrate your trustworthiness through your authentic interactions with people. Trust and relationships are outcomes of authentic working relationships, not prerequisites. In fact, I would argue, you can’t build a relationship with someone you work with separate from the work, and sometimes it’s harder to start working with someone you already know.)

Second is the idea that having a relationship with someone means knowing about them and their families and caring about them. But as the DRF makes clear, a working relationship that matters has five components: express care; challenge growth; provide support; share power; and expand possibilities. I know educators who are very proud of the relationships they have with students, but their idea of relationship is based only on that first criterion. The others are no less important and, again, can only emerge through the thousands of tiny interactions that happen on a daily basis. Respect, support, empowerment, inspiration—these things are not “one and done”, they are constantly being created, tested, and recreated, like muscles and neurons.

2. Individual traits are fixed and superordinate

It’s very tempting to explain and predict events using personal characteristics, or personality: honest, kind, arrogant, motivated, hard-working, shy, confident, and so on. We make these statements about people based on observations about their behavior (I infer that someone is kind based on the lovely card they sent me when I got that promotion; I infer that that boy is shy based on the way he hid behind his dad when I spoke to him), but those behaviors change with context. Motivation, for example, is not a fixed characteristic, it is a function of whether I believe I can do what I am being asked to do and whether it’s worth the time, resources and energy to do it. (I am highly motivated to help people when I think that what I can offer is a good match for what they need, because I know I will be pleased and happy when they are successful; I am not at all motivated to learn to knit, because I think it would take me a long time and I am not confident I would be good at it, even though it’s something I would love to be able to do.) The corollary of this fixation on fixed traits is that we underestimate the importance of the conditions in which people find themselves that promote or suppress any given behavior. For example, we believe that a kind person will stop to help a stranger in distress, but experiments have shown that whether they do or not is better explained by how much time pressure they are under; we believe that an honest person will not lie, but research shows that medical errors are significantly under-reported when the nurse or doctor will be punished for the error. We think of students as being well-behaved or not, but research shows that students are responding to the level of respect they experience in the learning environment. We should be much more purposeful about creating the conditions that will support the behaviors we want to see.

3. Differentiation is always an effective instructional practice

This is another idea that seems so obvious that it must be true. Many current educators were taught that they ought to be differentiating content, instruction, and/or assessment based on student interest, ability, learning style, and needs. I have no doubt that there are some places in the instructional program where differentiation is appropriate, but I also know that these should be narrow and targeted. Differentiation as an overall approach to instruction is too often a reflection of teacher expectations about what students will be able to do, based on what they have done in the past, on assessments which may or may not be salient, and which may or may not be a valid indication of what they can do with the current task.

Differentiation is often based on a couple of assumptions that have been debunked. First, there is the idea that we should be “meeting students where they are”, which is actually the exact opposite of what we should be doing, which is moving heaven and earth to ensure that students are working on grade level content; I highly recommend that you read this report, The Opportunity Myth, from TNTP. (It was a big influence on our development of the Accelerating Learning Framework; please read the article I wrote about Wilton’s use of that in The Learning Professional.) The one thing that bothers me about The Opportunity Myth is the perpetuation of the idea of teacher expectations as a mindset—OK, maybe more accurate to say that expectations is not only a mindset, whereas I think there are conditions we can create to operationalize high expectations that we don’t pay enough attention to—more about that in an upcoming Coaching Letter.

Second, there is the myth of learning styles, see below.

4. Learning styles is a thing

Yeah, no. Just stop already. The concept has no basis in psychology research, has been debunked multiple times, and yet incredible numbers of educators still say that knowing students’ learning style is important. For a brief history of the idea, see this article in The Atlantic and this piece by Daniel Willingham. I also have participants in workshops and coaching clients tell me that they are a certain sort of learner (“I’m such a visual learner!”) or that they are limited by their learning style (“I don’t have good executive thinking skills”). It matters because a lot of energy can be wasted planning for something that isn’t even real, and it can be really limiting to incorporate prescriptive and deterministic ideas about what you can or cannot do into your identity, or mindset.

5. Formative assessment is an event

Perhaps the most useful thing I can say here is that we need to stop thinking about formative assessment as a noun, and start thinking of it as a verb. It’s not a test, or any other kind of event. It is a process of understanding where students are in their understanding or skill development. Any time you hear someone talk about “giving” a formative assessment, you have to ask questions about what they think formative assessment means and how it should be used. Here’s a resource sheet I put together that might help. And your best source for all things formative assessment is always Dylan Wiliam.

Eventually I hope there will be a book, not exactly about HQI Live!, but about what we’ve learned about professional learning in service of high quality instruction—and a lot of that has come from HQI Live! This idea of letting go of outmoded ideas or faulty mental models—I think you could even call them myths—would be a section of the book, so if you have feedback about what I’ve written, I would be very glad if you would share it! My email address and cell phone number are at the bottom of every Coaching Letter, and if you get the Coaching Letter by email you can also just hit reply.

Thank you so much for reading The Coaching Letter! I am so grateful to be connected to so many leaders, coaches and educators! If there is anything I can do for you, please don’t hesitate to reach out. Best, Isobel

Relationships/Trust...You've given me a lot to think about there. I do wonder if there's a chicken/egg situation there: the more we learn, the more we trust and feel comfortable...the more we trust and feel comfortable, the more we learn. I wonder whether it's a bit of a fool's errand to believe we need to do either one first.

I appreciate this writing and will be back.

Looking forward to exploring the resources on formative assessment - thank you for compiling that!